Audubon Adventures

Background for Teachers

From the cold polar regions to the riotous green growth of a tropical rainforest, Earth is quilted with biomes—vast areas shaped by climate, geography, and plant life. The prairie biome, for example, is marked by hot, dry weather and wide-open grasslands. The boreal forest biome is a land of evergreen forests.

Within each biome are environments called habitats—the places where animals and plants of particular species live. North America’s prairie biome, for example, contains a habitat called tallgrass prairie, home to animals such as prairie chickens, badgers, and, in some places still, bison, which once were plentiful. This habitat lies in the wetter, eastern part of the biome, while the western, drier part is defined by short-grass prairie—the habitat of animals such as Burrowing Owls, swift foxes, pronghorns, and, in some places, bison.

A habitat offers animals the basics of life: sufficient food, clean water, and shelter. Many animals live in the same habitat year-round, so they also raise their young in it. Other animals migrate to different habitats after their breeding season is over.

Some species, such as coyotes, are “generalists” that can make a living in almost any habitat. Most species, however, require certain kinds of habitat in order to survive, let alone thrive. Efforts to conserve and restore wildlife populations go hand-in-hand with conserving and restoring habitats in which they live.

Habitat in Peril

The threats to healthy habitats include a familiar list of causes: urban sprawl, deforestation, development, agricultural conversion, overgrazing, invasion by nonnative plants and animals, draining of wetlands, pollution, and more. Looming over all these threats is climate change.

Climate change is a natural process that has occurred frequently during Earth’s long history. In modern times, however, this process has been accelerated by human activity, increasing the rate and extent of change.

Global warming is the steady rise in Earth’s temperature over time. Gases in the atmosphere known as greenhouse gases absorb heat and keep it from radiating into space. This is a good thing—Earth would be cold and uninhabitable without its blanket of warming air. But the greenhouse gases produced by human activities (such as burning fossil fuels) can cause the atmosphere to trap enough heat to raise Earth’s average temperature swiftly and steadily.

Read more.This rise in temperature reveals itself in many ways: melting ice caps, warmer oceans, retreating glaciers. And we’re bombarded daily with dire predictions: rising sea levels, increased flooding, drought, wildfires.

In 2009, “Audubon’s Birds and Climate Change Report” cited important evidence of climate change exhibited by North American birds. A study based on forty years’ worth of Audubon’s Christmas Bird Count data showed that 177 of 305 species are now wintering farther north than in the past. The average shift northward was found to be about 35 miles; more than 60 species moved more than 100 miles north. The shift correlates with a steady rise in January temperatures during that time. The 2014 “Birds and Climate Change Report” finds that shrinking and shifting ranges could imperil nearly half of U.S. birds within this century.

This northward movement may be in response to climate change, with birds expanding north to habitats that used to be too cold for them. This amount of shift in this short amount of time is very unexpected and indicates that warmer winters have already had a strong biological effect on North America.

Help for Habitats

The challenge of conserving habitat often seems hopelessly daunting. We’re besieged with dismal statistics about habitat loss or degeneration. But it’s important to note that people also use their power to change the world for good as well as ill.

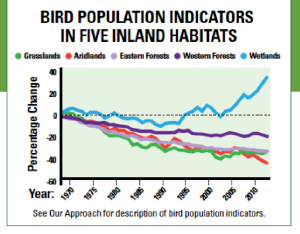

For example, efforts to protect millions of acres of habitat for ducks and other waterfowl have paid off: Audubon’s 2014 “State of the Birds Report” indicates that populations of 39 species described as indicator species are, in general, increasing. People nationwide, increasingly aware of the challenges facing the planet, are reducing fuel use and other product consumption, reusing products, and recycling what they can’t reuse. “Community scientists” are volunteering their time and expertise to count birds, monitor streams, and otherwise collect data to feed into studies. Others donate time and energy to removing invasive plants, planting trees, converting lawns into native bird gardens, and the like.

As the world’s human population grows, protecting habitat will continue to be imperative, for the health and the future of both wildlife and people.

Engineering, Technology, and Habitat Conservation

Engineering and technology might not be the first words that come to mind when thinking about habitats, but both are crucial to success in conserving, restoring, and protecting habitats. Scientists, conservationists, environmental engineers, and land planners follow the engineering design process when they identify habitat-related problems, and then pose, test, modify, communicate, and implement solutions to those problems. Technology such as instruments to monitor water quality, satellites to monitor land use, and computer programs to process data are used to identify and solve conservation problems.

Photos:(t to b) Larry Lynch/Audubon Photography Awards; iStock; Camilla Cerea/Audubon.

When settlers arrived in the midwestern United States, they saw grasslands stretching to the horizon. Since then, almost all the tallgrass prairie has been turned into farmland. Today barely 2 percent of this habitat survives.

When settlers arrived in the midwestern United States, they saw grasslands stretching to the horizon. Since then, almost all the tallgrass prairie has been turned into farmland. Today barely 2 percent of this habitat survives.